The Grand Mirror of Westworld

I’ve immediately latched onto Westworld, but not for the same reasons as some of my peers. Some mentioned the action, some mentioned the acting, and some mentioned the science fiction, but I think they were all missing the core. In my opinion, Westworld is (going to be) a show about existentialism that uses robots, and the wild west as simple plot mechanics. If people think this is only going to be like watching a life like twitch stream of someone playing Red Dead Redemption, they wont be able to see the forest for the trees.

Westworld is essentially a 1880s open world theme park full of robots (called hosts) that are seemingly identical to humans. Guests pay an exorbitant amount of money to visit, and they have completely and total freedom to whatever they please. They can choose to be the main character in some western heroic story line, rob the stagecoach and be a villain, or even get drunk at the saloon and party with the prostitutes. Being completely open world without punishment means guests can even rape and pillage to their hearts content. Something apparent very early on in the show is that the hosts endure the absolute worst of the worst.

Identity is Cumulative

The first episode opens with a change in software for the hosts that allows a subtle variance in the host’s display of emotion, but it essentially leads to a glitch that allows gives the hosts access to their past experiences, giving them partial long term memories, which are chock-full of trauma, tragedy, brutality, and, if the host is female, endless rape. The hosts have been protected from the horror only by their ability to forget, which has kept them inhuman but content.

In just the first two episodes, there are numerous times where hosts start to feel a sort of awakening. Awakening is a great way to describe it, because living with no memories and only with these pre-programmed drives is essentially a dream state for the hosts. As a side note, that’s also why it’s very hard in real life to become lucid in our dreams because nothing such as our past is present to cause us to question the current reality. In a way, this almost fully encapsulates the phrase ignorance is bliss. Because these hosts are living so in the moment, they are blissfully unaware of everything that has happened. These moments show a clear stark between the moments of procedure and the existential thought that becomes separate from ourselves.

This drives home a profound point that our Identity is not something inherent, it’s something historical, it’s something cumulative. It’s a canvas of moments in our lives, added to it by moments of joy, pain, suffering, tragedy, and as many more as there are colors. Overall, every color adds to it, sometimes we hold the brush and other times we aren’t, but the important point for many of us is to be aware that such a canvas exists when many don’t.

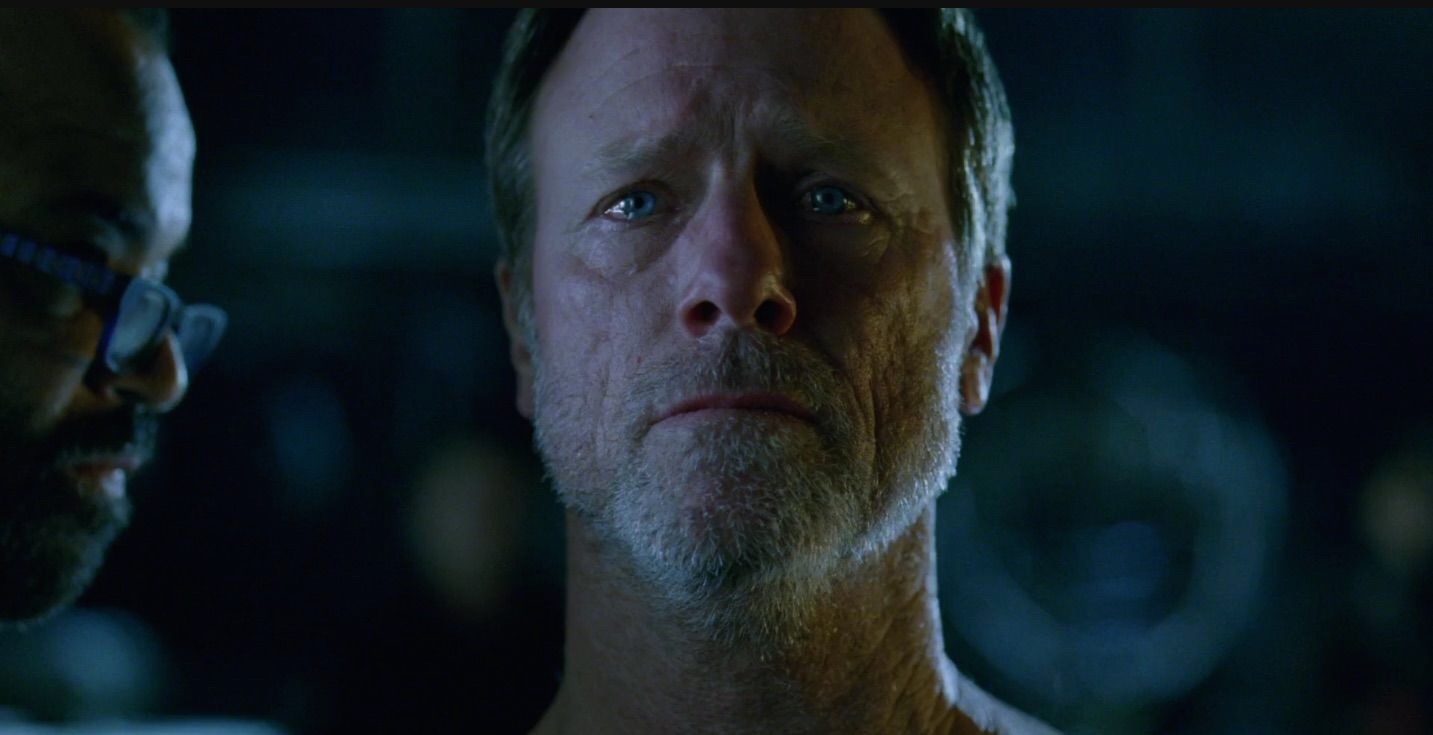

Peter Abernathy (played by Louis Herthum, a man who somehow steals a scene from Anthony Hopkins) is a very simple host with only 3 things that drive his artificial life. His farm, his wife, and his daughter, Dolores. In a moment near the end of episode 1, Dr. Ford (played by Anthony Hopkins) attempts to diagnose the glitch in his programming and walks him through the core things that drive him. When Peter is asked in that moment, he explains them and begins to say, “I wouldn’t have it any other way”, but stops before he can finish. While his robotic brain churns through possible alternatives is when it clicks. That’s when he begins to look through his memories and he begins to awaken. In his programming, he runs through older characters he’s played, but it’s not just a simple replication of those old characters in the present moment. By having access to them, by being aware of them, they change his view of the present and he becomes something different entirely. Like a swinging pendulum back and forth from two directions to settle on a third in the middle which alters his desire to a simple one, meeting his maker. It’s very Frankenstein-esque, being angry and desiring to kill his maker for creating him against his will in such a world of anguish. In frustrated moments of existential angst, I’ve certainly felt as if that’s relatable, but definitely not to that degree. No one asks for an existential crisis, so it feels like someone else is the cause of their pain. It’s no stretch of the imagination that if Peter was left by himself, he might attempt to end his life, if that’s what you want to call it.

But where Peter has an awakening in almost an instant, there are other characters who’s awakenings are far slower such as his daughter Dolores. The constant theme of flies is present throughout the entire first episode where they land on faces of hosts and even crawl along their eyeball without any response from them. It would make sense that they probably don’t have any programming present to deal with a wildcard such as a fly, but in the final moments of the episode, she kills one on her neck in one quick slap. Killing the fly seems to suggest that this entire process of becoming self aware requires a historical stimuli. It begs the question how many other hosts are subtly and slowly becoming aware?

Life Inside the Piano

Another constant theme I picked up on so much is causality. In the opening intro, we see a robot’s hands playing the piano, but when the hands lift away, the piano keeps playing. So it only appeared to be playing the piano, it makes you wonder what other logical assumptions we make about our reality and the one in the show that end up being completely false. David Hume famously pointed out that we can’t actually prove causation, we can only observe what consistently looks like causation. Shots of automated player pianos are scattered thought the first two episodes which make me think if this idea of false causality will end up being a bigger element in the show. The Man in Black (played by Ed Harris) is a guest of the park who’s been coming for over 30 years. He’s finished almost every story line there is in the world, but he’s trying to find the endgame and is convinced there’s another maze or quest that’s deeper that no one else has finished.

In episode 2, while interrogating one of the hosts, he says, “You know why this beats the real world? The real world is just chaos. It’s an accident. But in here, every detail adds up to something.” There’s something poetic about that. While many of the characters on the show are waking up to the chaos of reality, one of the characters enjoys the blissfully false one. The entire first episode is narrated by Dolores where she speaks about the beauty of order and purpose, it only makes sense that there are some out there outside of it that want in. Don’t get me started on Dr. Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins), who is the creator of the park and who’s storyline is still mysteriously up in the air given how early on it is. However, if I were to make a prediction, I would guess he is in the same boat as The Man in Black or is purposefully altering the hosts to become self aware for some deeper reason. We will see though.

We Are The Robots

I admit, there were many times in the second episode the show tickled a MMORPG sensation in me. Showing up to a new town, hearing all these open quests proposed by the Hosts/NPCs. One could even view the show as a sort of moralistic indictment of our deepest and darkest desires when faced with zero retribution. Back in college, there were a couple research projects I was involved in that explored this profound difference between why people act differently online rather than in person. Anonymity has always been inherently entwined with freedom from punishment, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth” has always been one of my favorite quotes from Oscar Wilde.

As an avid Grand Theft Auto player, I’ve always nervously pondered philosophically about how I was capable of driving a car through a crowd of digital people and not feel anything about it. In GTA V, there was a first person camera angle where I did the same, but it actually felt a few degrees more realistic since I was viewing through the actual drivers seat. My reaction was far different, and to be honest, it was a little jarring. It wasn’t until I dug more into the sliding scale of Anthropomorphism that I noticed how our reaction changes the more realistic a simulation becomes. In episode 2 of Westworld, William (played by Jimmi Simpson) is a first time guest to Westworld and pertinently asks the concierge if she’s a real person or a robot. Her thought provoking response is, “If you cannot tell, does it matter?”

That angle is interesting and as much as we relate to William’s hesitance with everything because like he, we are new to this universe, Westworld isn’t going to be 10 hours of only “humans are rapists and murderers”. It’s ascending the stairs of self realization almost immediately. However, we might be mistaken if we look at the guests or the employees of the park are sort of a symbolic identification. If there’s a character or a hero we as the audience are supposed to connect with, it’s the hosts, not the people.

Many might not pick up on it and that’s perfectly fine, I’m not attempting to be an intellectual snob whatsoever, but for people who haven’t done that in their own lives, people who haven’t examined their own reality and pulled themselves out of the bliss of the moment might miss it. I say I think, because I could be completely wrong about Westworld since only 2 episodes have aired, but I see Westworld as a grand mirror that allows us to look at ourselves and see our reality in a different way and to question it. By telling a story in which robots question the nature of their reality, Westworld is hoping to get us to begin questioning the nature of our reality.